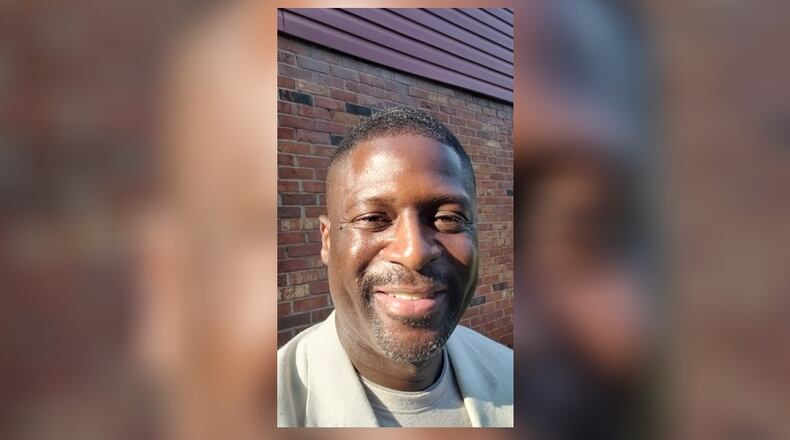

Cedric Howard, who for years had been busy making his mark in the business world after playing basketball at Patterson Co-Op in the mid-1980s and then graduating from Bowling Green State University, stopped by a local nursing home one day nearly a decade ago to visit his aunt, Doris Corbitt, who was well into the advanced stages of Alzheimer’s Disease.

She had worked for a North Dayton electronics manufacturer, but now was bedridden and no longer could speak.

Caring for her that day — as she did every day — was her sister and Cedric’s mom, Minnie Howard.

Minnie was doing the same for her and Doris’ mother — the nonagenarian Gussie Huff — who was struggling with Alzheimer’s, as well.

Gussie was Cedric’s grandmother and he remembered how vibrant she had been into her 80s:

“They lived on Williams Street (in West Dayton) and every Saturday she’d take the bus downtown and shop and then ride the bus back home again.”

While she still could speak and read as her Alzheimer’s progressed, she would no longer eat.

For 10 years Cedric’s mom, who had worked 34 years at the GM truck and bus plant in Moraine before retiring, cared for the women and, as it turned out, many other dementia patients, as well.

“That day in the nursing home, I suddenly heard my mom’s name called over the intercom,” Howard said. “It was like ‘Minnie Howard, come to (such and such) room.’

“I said, ‘Mom! What’s going on? Are you working here?’

“She said, ‘No, but I want to make sure my sister is taken care of. So many people here need help. This is what I want to do.’

“And the next thing I know, she’s down the hall taking care of somebody else and then someone else after that. She was just getting them whatever they needed and making sure they were OK.

“That was the beginning for me. It spurred a spirit in me. I wanted to help my mother any way I could.” But first, Howard said, he needed to find out just what he was dealing with:

“At the start, I was like, ‘What is Alzheimer’s exactly? I wanted to know more about it.”

He soon discovered:

»Older African Americans are twice as likely as older whites to have Alzheimer’s or another dementia.

»Among Black Americans 70 and older, 21.3 percent are living with Alzheimer’s.

»There is a 43.7 percent risk of relatives of Alzheimer’s patients getting some form of dementia themselves.

»Most sobering was the realization that, as of now, there is no cure.

His Aunt Doris died in 2015.

His grandmother passed away a year later and her loss was especially numbing to the family he said:

“After I learned some of the facts and saw what the disease did and watched how my mom did everything she could to help, I knew I had to do whatever I could, to.

“I had to do something.”

Basketball event

For nearly a decade Howard has done so in more and more impactful ways, but nothing like he and his Making Memories Foundation — with the help of The Dayton Foundation, the Miami Valley Chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association, Sinclair Community College, well-connected community members like Michael Carter, Sinclair’s Chief Diversity Officer and the former Trotwood Madison and Springfield South high school hoops coaches; Ty Fields, the University of Cincinnati teacher and the founder and president of the S.T.A.R. S. Youth Enrichment Program of Dayton; and some impressive figures from the basketball world — have planned for early next week as the City of Dayton readies for the First Four.

On Monday, March 13, at Sinclair’s Great Hall, Making Memories will present a “Night with Mike Jarvis,” the legendary college basketball coach, TV sports analyst and author. He will be accompanied by several other college and pro basketball figures.

Along with Jarvis’ keynote address, there will be a dinner, an Alzheimer’s information session and a silent auction.

The 6-8:30 pm event is free to the public, but donations that will go to Alzheimer’s research are encouraged and will be greatly appreciated, Howard said.

Jarvis, who in his 25 seasons as a head coach at Boston University, George Washington, St. John’s and Florida Atlantic took 15 teams to the NCAA and NIT tournaments, some making deep runs, will speak about his career and some of the athletes he’s coached (including Patrick Ewing in high school and Michal Jordan in Team USA hoops).

He also will present some of the tenets from one of his books — “Skills for Life” — and he’ll likely talk about someone he lost to Alzheimer’s.

He will be preceded on stage by several notable hoops figures, including Dayton Flyers women’s coach Tamika Williams-Jeter, who has her own Alzheimer’s story.

Howard said Jarvis will be joined by former basketball players like Dale Ellis, the Tennessee All-American and NBA All Star who spent 18 years in the league; Dennis Hopson, the former Ohio State star and longtime pro who’s now the Lourdes University coach; former Buckeyes standout Troy Taylor; Sedric Toney, the Wilbur Wright High and University of Dayton great who spent seven years in the NBA and David Greer, the Bowling Green Hall of Famer who had a long career as the Wayne State head coach..

Along with the hoops talk and a Jarvis book signing, there will information about the latest news on Alzheimer’s research and 10 warning signs of the disease.

Those wishing to attend the event must register by Wednesday March 8. For more information or to sign up, visit: https://linktr.ee/supportmiamivalleyalzheimers.

And then on Tuesday, March 14, Jarvis and the other basketball notables will hold a clinic and will discuss the landscape of the high school and college game. It is intended especially for high school and college coaches, players, athletic administrators and referees.

‘You must give back’

This will be the first in what Howard hopes will be a yearly winter event that complements his annual golf tournament each summer.

This year’s June 19th “Making Memories Golf Classic to End Alzheimer’s Disease” -- his ninth links venture – will be played at Walnut Grove Country Club. Last year’s event raised $10,000

For more information on the golf outing visit www.golf2endalz.com

Howard — now a manager at Oak Street Health Clinic on Wayne Avenue — fully embraces a mindset he learned from his parents, Minnie and Lee Howard, who have been marred 55 years:

“In order to be a complete person, you must give back.”

He often has done just that.

He’s a former board member of the African American Community Fund of The Dayton Foundation and for the past 16 years he’s been on the board of the Miami Valley Crime Stoppers.

But nothing he’s done has been quite like this.

“This is my mission,” he said the other night. “Some of the people I looked up to are no longer here. They’re gone. But I can walk in their footprints.

“And when I’m no longer here, I want this to continue with the research until they find a cure. I really want to leave something.

“I want to have made a difference.”

He need not worry.

He already has.

About the Author